The first battle of Ypres took place in the late autumn of 1914 and was part of the 'race to the sea'; the Germans tried to outflank the British and the French by sweeping around behind them and cutting off the English channel. The British stood their ground at Ypres and prevented the Germans from capturing the town.

The second battle took place in April 1915 and involved the first large use of chlorine gas in the war (contrary to the Hague conventions, which outlawed the use of gas in war). The Germans were trying again to seize the town of Ypres.

They achieved initial success as French troops fled the fumes, but failed to take advantage before Canadians plugged the hole in the lines. When they attempted a gas attack against the Canadian soldiers, one of our medics (Lieutenant George Nasmith, a chemist by training) identified the gas and came up with a solution: urinate on rags and hold them over your nose. The urine filtered out the gas, the Canadians held the line, and the Germans were prevented from taking the town.

The third battle in the fall of 1917 was an attack by British forces to push the Germans back from Ypres and capture a submarine base along the Channel. The first goal was to capture the nearby town of Passchendaele; Australian and New Zealand soldiers made a lot of ground but were taking enormous losses from German machine guns. Eventually Canadian troops were brought in and they captured the village--but at a tremendous cost.

Finally, in the fourth battle in spring 1918, the Germans launched a desperate offensive to take Ypres. American troops were steadily flooding in and the Germans were doing everything possible to win the war quickly. All of the ground taken in the Battle of Passchendaele was abandoned during this battle, but the Germans were successfully stopped by the British.

Not once in the entire war did German soldiers enter Ypres, but the town was completely flattened from artillery strikes by 1918.

204,810 Commonwealth soldiers were killed in the Ypres Salient over the course of the war. Of these, 54,866 are missing graves; they disappeared into the Belgian mud.

We took a tour of the battlefields on our last day in Ypres.

Our first stop was the cemetary located at the medical station where John McCrae worked. For those unaware, McCrae was the Canadian medic who wrote In Flanders Fields, the most famous war poem ever written. He wrote it on a scrap of paper in May 1915, while down in the trenches amidst German shelling. A good friend of his had been killed the previous day.

The medical bunkers are still there, kept in their original condition.

A plaque to McCrae.

War graves.

The grave below is for a soldier who was fifteen at the time he was killed.

We next visited the Langemark German war cemetary, one of the few German cemetaries to survive the wrath of the Belgians after the war ended. Langemark is particularly known for the thousands of German students buried here. During the First Battle of Ypres they marched in confidently singing German anthems; completely inexperienced as fighters, they were slaughtered by well-trained British troops.

There are 40,000 Germans buried in this cemetary. 29,000 are in one mass grave in the center.

German bunkers, still standing.

A memorial to the students; the "innocents".

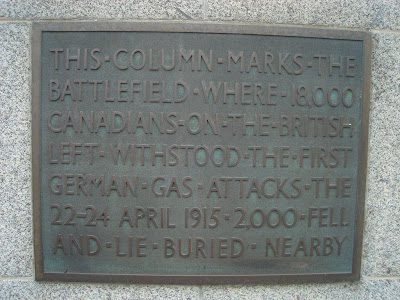

Next stop was Vancouver Corner, or the Saint Julien Memorial as it's officially known. It marks the spot where Canadian soldiers were attacked with gas during the Second Battle of Ypres.

The statue is called the 'Brooding Soldier'.

The plaque on the memorial:

This is Tyne Cot Cemetary. It's the largest Commonwealth cemetary in the world, for any war. There are just under 12,000 graves here. 966 of them are Canadian.

Around the back of the cemetary is a memorial to soldiers whose bodies were never found. It's actually a chronological continuation of the Menin Gate memorial, which cuts off at August 15, 1917.

This picture was taken standing on top of the Cross of Sacrifice, in the center of the cemetary. The Cross is built over top of a German pillbox whose capture was the primary goal of the Australians and New Zealanders during the Third Battle of Ypres. The soldiers would have been charging up the hill, directly towards the camera.

The plaque underneath the Cross of Sacrifice:

One of the graves here contains the body of James Robertson, a Canadian soldier who won the Victoria Cross during the Third Battle of Ypres. While attempting to capture the village of Passchendaele, he charged directly into a German machine gun post in order to save the lives of two other Canadians. He was killed in the process.

Underneath this grave are five bodies; the only thing known about them is their nationality.

Our final stop was the Hill 60 Museum, where a system of trenches have been preserved.

A couple of British guys on the tour with us actually went exploring inside the tunnels; they're braver than me!

These photos and captions were taken from the website of the Canadian War Museum.

Canadians Advance

Canadians of the 29th Infantry Battalion advance across No Man's Land through the German barbed wire during the Battle of Vimy Ridge, April 1917. Most soldiers are armed with their Lee Enfield rifles, but the soldier in the middle carries a Lewis machine-gun on his shoulder.

Passchendaele Mud

Mud, water, and barbed wire illustrate the horrible terrain through which the Canadians advanced at Passchendaele in late 1917.

Draining Trenches

In rain-soaked northern France and Belgium, trenches during much of the year degenerated into muddy ditches. This added to the misery of trench life, and could also result in the collapse of trench walls and parapets.

Untended Canadian Graves

An overgrown cemetery of untended graves. The informal white cross on the right contains the names of three members of the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry killed in 1918: Private J. Sweeney, Private J. Coetzee, and Private D. O'Keefe.

Gas Attack on the Somme

Aerial photograph of a gas attack on the Somme battlefield using metal canisters of liquid gas. When the canisters were opened in a stiff, favourable wind, the liquid cooled into a gas and blew outwards and over the enemy lines. Strong concentrations of gas could overwhelm respirators, but a change in wind direction could also reverse the cloud, which then gassed one's own troops.